The battle over who will dominate the Constitutional Commission is underway in Egypt. With a Presidential election being held at the same time, there is an atmosphere of chaos. Amal Wahab is the Cairo correspondent for the Norwegian daily Klassekampen, which published this piece on the weekend.

The battle over who will dominate the Constitutional Commission is underway in Egypt. With a Presidential election being held at the same time, there is an atmosphere of chaos. Amal Wahab is the Cairo correspondent for the Norwegian daily Klassekampen, which published this piece on the weekend.

On Saturday, the parliament began efforts to choose a constitutional commission of 100 people, who will write a new constitution for the post-revolutionary Egypt.

“The referendum and the subsequent constitutional declaration from last year, has planted the seeds of a deep division among the people. A struggle of wills is underway”, Hassan Nafaha, Professor of political science told Klassekampen. Nafaha claims that the country is in an important phase in the workings between the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary forces

After Mubarak was deposed in February last year, the Islamists agreed to a vote on constitutional amendments in 1971 constitution, while the secular forces of the right and left wanted a new constitution. The Islamists won the argument, in what many claim was a secret agreement between the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Nine sections of the Constitution were amended and put up for a vote. Over seventy percent of Egyptians voted for those constitutional changes. That should have meant that the amended 1971 Constitution would be the country’s constitution during the transition period. According to this constitution, the SCAF would have to transfer power to the leader of the country’s Administrative Court.

Instead, the SCAF issued what they called the Constitutional Declaration which, in addition to the nine modified sections Egyptians had voted on, included fifty-four paragraphs Egyptians had not voted on. The Declaration established that there would be parliamentary elections in November 2011 and that this parliament would be asked to choose a constitutional commission of one hundred people to write the new constitution. The Declaration places no restrictions on the parliament as to how the Commission should be selected to ensure that it is representative.

“Since there is a lack of guidelines for the Commission to be selected, these will have to be negotiated among the factions in parliament. This will no doubt take time, and it is unlikely to be in place before a new president is elected”, says Nafaha.

In the absence of guidelines on selection of the Commission, there is a genuine fear that Islamists in the country will seek to dominate the design of the new constitution. The Liberty and Justice party, which is the political wing of Muslim Brotherhood, together with the newly established Noor Party of the Salafi movement, presently occupy seventy percent of the parliament’s seats. The Brotherhood was established back in 1928 and has since been an active player in the opposition. They reaped the fruits of decades of social and political work in the elections of last November, and were elected as the single largest party.

The Egyptian newspaper al-Masry al-Youm has reported that the Brotherhood wants forty percent of the Constitutional Commission to be elected members of parliament. The Liberal party has proposed a maximum of twenty-five percent, while the leftist Tagammu party argues that the members of the Commission should be selected from outside the Parliament (the idea is that a constitution should include all and not be written by and for the majority in parliament). No one doubts that an Islamist domination of this process can change the country radically in the years to come.

The requirement for the election of the president at the same time makes the process even more difficult. On this, too, Egyptians are divided.

In the wake of abuses since Mubarak’s fall, including the loss of hundreds of lives, angry protesters have demanded that the SCAF transfer power to a civilian authority as soon as possible. For their part, it has been suggested that the SCAF fear they will be subjected to prosecution and financial scrutiny once they leave power and that they want to consolidate what remains of the Mubrarak regime and reduce the damage from the January revolution.

Under pressure from the street, the SCAF decided to launch presidential elections. Candidates had until 10 March to register, presidential elections will be completed by 21 June and the new president will assume office no later that 1 July. Candidates from parliament have certain advantages in attempting to run for president, as MPs can be nominated by their own party. If you are not an MP you must obtain written support from thirty MPs or 30,000 official endorsements from people in several different counties.

The present crop of presidential candidates are, according to Nahafa, either “Islamists with no party affiliation, former key persons in the Mubarak regime or completely unknown independent people.”

Nafaha believes it is problematic that the election of the new president will take place simultaneously to the new Constitution being created. “First, according to the Declaration, the parliament, has all of six months to agree on how the Commission should look, and another six months to write the new Constitution and put it up for a vote in a referendum.” If the the Constitution should be ready before the presidential election, it means “that the country’s fundamental documents will be nailed together in all haste. We may end up with a bad constitution, and an even more miserable president”, he told Klassekampen.

“Egypt is at a crossroads. Either Egyptians will succeed in putting in place a constitution and a president worthy of the new post-revolutionary Egypt. Or the counter-revolution will succeed in reproducing the old regime, in a slightly sleeker form, and continue as before.”

Amal Wahab

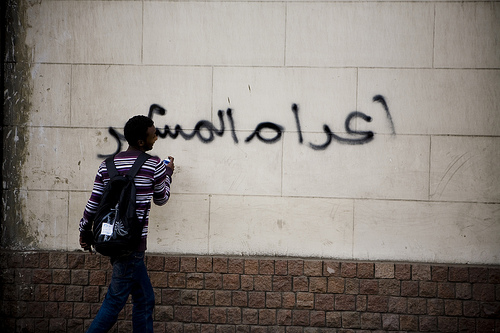

Image: anti SCAF grafitti Hossam al-Hamalawy