Iceland’s former prime minister is in court for things he didn’t do. To be precise, he is charged with four counts of not doing what he should have done, under the laws on ministerial responsibility. Herdis Sigurgrimsdottir explains.

Iceland’s former prime minister is in court for things he didn’t do. To be precise, he is charged with four counts of not doing what he should have done, under the laws on ministerial responsibility. Herdis Sigurgrimsdottir explains.

The case of former Prime Minister Geir Haarde is as intriguing as it is unprecedented. The principle of government ministers being personally responsible for their actions – or omissions – has been part of the Icelandic constitution since 1905. The law on ministerial responsibility was approved in 1963, but no scandal in the country’s political history has prompted a serious discussion of invoking this constitutional amendment. That is, not until the collapse of the bulk of the Icelandic finance sector in 2008 nearly caused national bankruptcy. (For a recap of Iceland’s financial crisis see this BBC article)

But how much of the burden of responsibility falls on Haarde personally? After all, he served less than half a term as prime minister, taking over when the banks were already approaching ten times the size of the national economy. And, since he is charged for things he didn’t do, his is a case of counterfactuals and ‘what-if’s. Can one politician really be held accountable for a systemic failure?

First, the law.

The concept of ministerial responsibility comes into Icelandic legal and political tradition from Iceland’s former colonial master Denmark, as does most of the Icelandic legal tradition. (Iceland gained independence from Denmark in 1944.) The law stipulates that a government minister can be held personally accountable for gross misconduct or otherwise jeopardising the national interest by their actions – or lack thereof – while in office, including “if [they] neglect to do that which might avoid such jeopardy”(art 10.b).

Enter the speculations and the counterfactuals.

On suspicion of such misconduct, an extraordinary justice procedure comes into action. The parliament will have the allegations investigated and then vote on whether to press charges or not. In this case, the parliament voted to drop charges against the former ministers of foreign affairs and of commerce, but proceeded to press charges against the former prime minister. The hearings started on Monday 5 March and the court hopes to hear all witnesses by mid-March.

The case will be tried before the extraordinary court called Landsdómur which is comprised of 5 supreme court judges, a district chief justice, a constitutional law professor, and 8 representatives elected by Althingi, who don’t necessarily have a legal background. This is in fact a pure and simple example of checks and balances, where the executive power is held accountable jointly by the legislative and the judiciary.

The Danish political tradition has a similar process which has only been used once in the past 100 years. In what is commonly known as the Tamil case, minister of justice Erik Ninn-Hansen ordered that Tamil refugees’ applications for family reunification be stalled in the system. The court of impeachment (Rigsretten) found that Ninn-Hansen had abused his ministerial power by giving an illegal order.

But ruling on an action seems much more straight-forward than ruling on a lack of action. The burden of proof is completely different. Instead of proving that an action was taken and determining that it is illegal, it revolves around proving that a better option was possible and feasible at that time. With hindsight, we now know what actions might ideally have been taken, but were they the most sensible options given the information at hand? And were those options really available at the time?

To take an example, Haarde is charged with not having initiated state pressure on the banks to reduce their size, for example by selling off some of their assets. His response is to ask How could that have been done? The market was already difficult in early 2008 and selling off assets at lower than market price might have confirmed the rumours that were already circulating about the vulnerability of the Icelandic banks. such action might have precipitated the fall of the banks, not saved them.

It is a defense of ‘Damned if you do, damned if you don’t’. To what extent can one man be held accountable for the options he didn’t take in a situation with few good options, with the pressure of time and without the gift of hindsight or omniscience? The difficult task of determining this rests with Landsdómur.

Herdis Sigurgrimsdottir

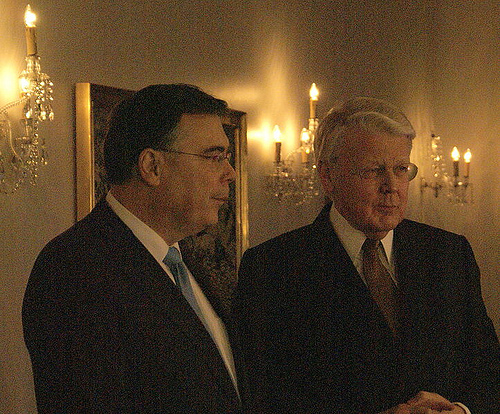

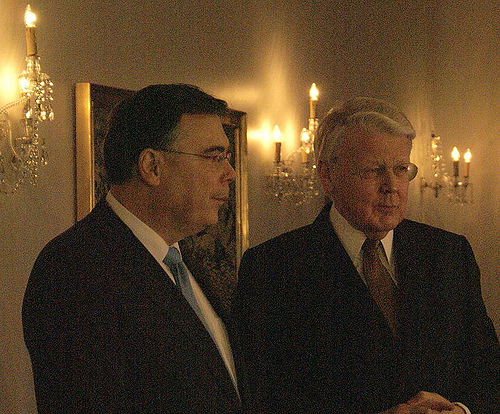

Image: Haarde (left) and President Ólafur Grímsson by álvarozarzuela