Today, the Supreme Court of the United States begins hearing arguments in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Shell, a landmark case in the struggle to hold business entities accountable for human rights harms committed abroad.

Today, the Supreme Court of the United States begins hearing arguments in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Shell, a landmark case in the struggle to hold business entities accountable for human rights harms committed abroad.

The case involves allegations by members of the Ogoni people of Nigeria that Shell assisted the Nigerian government in torturing and executing Ogoni activists in the 1990s. Many Ogoni were opposed to the company’s operations, claiming that drilling operations were having a devastating effect on their health and the environment. The suit is named for one of the plaintiffs, Esther Kiobel, who is a widow of one of those killed. Other plaintiffs are victims of torture themselves.

In September 2010, a court of the US Second Circuit dismissed the case on the grounds that only individuals, and not companies, could be liable for violations of international law. The decision was a surprise. It was contrary to over three decades of human rights litigation in the US under what is known as the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA). ATCA – or the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) as it is often referred to – allows law suits to be filed in the US for violations of international law committed abroad. US courts have long allowed suits to be heard against companies under ATCA, but a divided (2-1) Second Circuit court argued that since international law does not apply to companies, companies could not be sued for such violations under ATCA.

Kiobel has “precipitated a wave of activity from other appellate courts rebuking the Second Circuit’s conclusions and isolating its reasoning”, but the fear remains that the Supreme Court will act to defend corporations. For US observers, there is a bitter irony in the possibility that a conservative Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of business in the Citizens United decision on the grounds that corporations enjoy the rights of persons, could rule in Kiobel precisely the opposite. For Peter Weiss, one of the originators of human rights litigation in the US, the Supreme Court could end up “treating corporations like people to let them make unlimited political contributions, even as it treats corporations as if they are not people to immunize them from prosecution for the most grievous human rights violations.”

Such a decision would mark a significant step backwards in efforts to clarify social responsibilities for business alleged to be involved in the worst kinds of human rights abuses. ATCA has led the way in what has become a world-wide trend in the domestication of international crimes – both in criminal law and as harms in tort law – including their applicability to business entities. The practice has now reached around the world: research at the Fafo Institute involving a comparative study of sixteen jurisdictions found what Professor Anita Ramasastry and former EPA lawyer Bob Thompson and I described as an “expanding web of liability for business entities implicated in international crimes”.

One finding from the research was that courts in different countries have their own rules about jurisdiction and they apply these to the task of adjudicating international norms or prohibitions domesticated from the international law. The normative prohibitions are universal, and each jurisdiction has its own way of incorporating them, but they do not read jurisdiction from those international substantive norms, as the US Second Circuit seems to have done. For example, in the few civil law countries which excluded legal persons from criminal prosecution, they did so for long held reasons of their own and with no reference to international law (Spain even recently reversed this principle in 2011). There is no evidence that courts in other countries would exclude civil claims against companies arising from international crimes, just because they were international in origin. None of the countries studied would exclude legal persons from the personal jurisdiction of their courts on the grounds that international law does so (which is a debateable point in itself).

The Long View

In the decades of debates about business responsibility for human rights, one responsibility of business has remained universally uncontested: companies should obey the law in the jurisdictions in which they operate. For many years this meant companies could ignore human rights in war zones or dictatorships and still obey the law; because human rights protections were either non-statutory (declarations but not legislation), not enforced or non-existent.

ATCA has enabled US courts to play a role in ending that impunity. It has been far from a perfect solution. In fact, it is a solutuion that has evolved in order to meet a very real need for which government has yet to properly legislate. If the ATCA option is lost, it is likely that the number of cases being pursued in other jurisdictions will only increase (and that US lawyers will take their cases forward at the state level, rather than in the Federal Courts). This is happening already, although there are very significant obstacles to justice for victims of business-related human rights harms.

But the significance of a regressive decision on Kiobel is not just that it may shut down an important avenue for access to justice, but that it will do so in a way in which the rule of law in the United States will have so obviously succumbed to the laws of rule.

The movement to end impunity is not an inevitable process. There has been significant progress in the past twelve months in defining the nature of business responsibilities in relation to human rights. But there is hard grassroots political work to be done to get states to take the necessary next steps to ensure corporate respect for human rights, and, not least, to prosecute – or allow suits against – those companies who insist on ignoring the laws governing international human rights crimes. The Supreme Court cannot stop that movement. But it can certainly hurt it.

Update: you can read the transcript of the oral arguments by clicking here. It is not particularly happy reading, as the statements and questions by the Justices do not seem predisposed to the arguments for accountability of corporations under ATCA.

Update: (4 March) Earthrights International Legal Director Marco Simons reports the Supreme Court has delayed ruling on Kiobel and will re- hear the case, possibly to avoid ruling directly in favour of corporate immunity for torture and extra judicial killings. watch this space

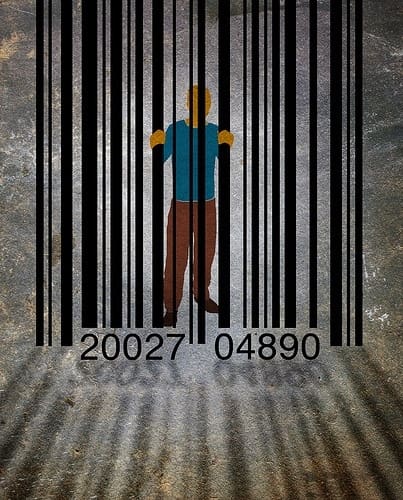

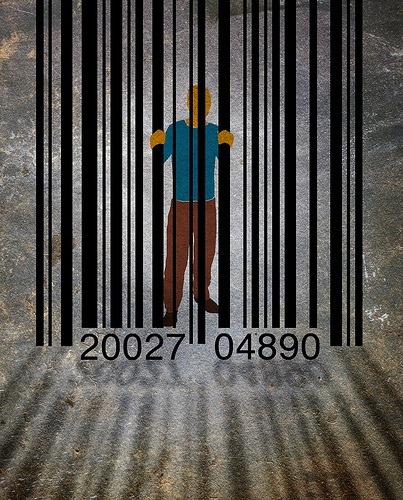

Image: Jared Rodriguez / Truthout